- Home

- S. , Sindhu

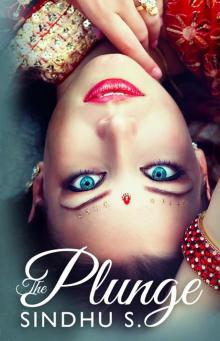

The Plunge Page 10

The Plunge Read online

Page 10

The picture was misleading, certainly a case of careless misrepresentation. Siddharth would have agreed.

.

16

CHAPTER

Bickering

Unlike during the last visit, this time, Siddharth looked cheerful.

Had he gained some weight? Maybe it was because she was seeing him again after almost three weeks.

“Let’s go to Prospect Hill,” he said as they walked towards the parked car. “We’ll get a captivating view of Shimla in the late evening,” he said enthusiastically.

“Do you know how the hill got its name?”

“Oh yes,” she said. “Ajay told me. We visited a few temples last week. I have done quite a bit of wandering over the last two weeks.”

She surveyed his face for a response. The tense muscles suggested he could be suppressing a frown.

“I have come to like research,” she said and looked at Siddharth. Was he with her? He seemed lost in thought. Why did his mood change so abruptly?

She tried to engage him in conversation. “But research is also exhausting.”

He nodded in agreement. No smile.

“It’s fun to meet people and listen to their stories. Something like journalism, but without any deadlines or bylines,” Anjali said, searching for some interest in Siddharth. He was staring at the sky. There was still no comment.

“Only in research, you are free to reach conclusions. For example, from my experience so far, I can safely say that the native Himachalis are uncomplicated.”

The next minute, she remembered Siddharth’s wife was a Himachali. It made her somewhat insecure. She clung to his arm, and sniffed as if to make sure he was there with her, which brought a smile to his face.

“The first phase of research is also the most tiring, says Ajay,” she began excitedly until he interrupted.

“What kind of information did you need for your project from Prospect Hill?” His tone implied irritation.

“I was looking for the history of the temple, was curious about the name Prospect Hill,” she said. But why was she sounding apologetic?

It was the first time she had ever seen him irritated over something unrelated to his life. Was he being possessive? The thought made her feel valued.

She was five years older than Ajay. But they had common interests, which had drawn them closer. His slight build, beard, and glasses gave Ajay a nerdy look. At times, she suspected that he forgot to comb his hair. But there was nothing serious about their bonding that needed to be mentioned to Siddharth.

Anjali nudged Siddharth. She smiled joyfully as her arm rubbed against his hairy forearm. She felt a desperate urge to hug him as they walked past a group of tourists. She became just a human body in a crowd. When surrounded by an ocean of similar bodies, the only feeling a lover can have for a partner is perhaps lust.

When did she start regarding lust as an acceptable feeling?

Siddharth maintained his seriousness even after they reached the parked car. Anjali nervously bit her lower lip when Siddharth opened the door and took the driver’s seat. Anjali rubbed his shoulder. He looked at her startled, as if awakened from an unpleasant dream.

“Is this Ajay the same research fellow I had seen with you during my last visit?” he asked.

“Yes, the one with beard,” she said with a smile.

“Oh.” His response was more of a reproach.

“What is his research topic? Anything related to your project?” he asked, knitting his brows, as if trying to spot an important landmark at the farthest end of the road, steadying the steering.

Siddharth preferred to drive a rental car. He was not comfortable with taxis.

“It’s about how the older generation adjusted to the change in the hills over the years. Interesting, isn’t it?”

Siddharth shrugged. He did not seem as impressed with the idea as she was. The shrug meant that either he was not sure or he was not convinced. Anjali could not decide.

“Please drive slowly,” she said as they drove up the steep road leading to Prospect Hill.

Not the right time. Had he been in a better mood, she would have reached for his hand again.

The small temple of Kamna Devi was a favourite tourist spot. The goddess granted wishes, according to locals.

Siddharth parked the car.

The temple was pretty basic, like most others in Shimla. The stone idols were elaborately draped with garlands. The smell of burning oil lamps and incense sticks transported her into another world. She felt safe and calm.

Anjali knelt down before the priest. The old man mumbled some prayers for her and smeared the red holy powder, tilak, on her forehead. She offered some money to the frail man.

Siddharth was waiting for her outside the temple.

Leaning on the half wall, Anjali admired the breathtaking view of the distant town below.

“It looks better at night,” he said. “In fact, this spot offers one of the best night views of Shimla.”

“It really is the best place on earth at this moment,” she said, moving closer to him. He smiled and pulled her towards him.

.

17

CHAPTER

Sleepwalk

Anjali turned around and smiled. It melted something within Siddharth. It always did; the furtive look was irresistible.

Why did she have to be so charming? She should not hang around with Ajay. She was too gullible. Anjali should be warned.

That night, Siddharth watched Anjali for a long time in the faint light of the night lamp.

Why did Anjali feel so insecure at times? Was she always like this?

The more he knew her, the more intrigued he became.

She looked much younger than her age. She could easily find a young husband. She said she didn’t believe in marriage. “Marriage is a huge gamble,” was her argument.

What if she meets her man one of these days? The idea made him uneasy. But, she, too, deserved a committed relationship.

Siddharth placed a protective arm around Anjali. She was sleeping on her side, facing him, vulnerable. She responded to his caress instantly and snuggled against him. He kissed her on her forehead, which woke her up. She yanked her kurta off and hurled it onto the chair near the bed. He enclosed her in his arms. He liked the way she moaned under his body.

“Indeed, slow eaters make good lovers,” she said in his ears.

“OK, that sounds like a compliment,” he whispered back.

She giggled. It brought a smile to his face.

“Have a look,” Anjali said with enthusiasm, handing over her notes to Siddharth.

Siddharth kept his morning tea on the side table and took the notepad from her.

“The British must have had great patience and taste,” she said.

Under the title ‘Colonial Exploitation’, she had scribbled: The difficult terrain did not hinder the British will to replicate familiar architecture. They were good planners, architects, and smart administrators, but certainly bad masters.

According to jottings in Captain Mundy’s Journal of a Tour in India, Indians were punished with lashes in public: in one instance, as many as 800 for a fight with a British official. Indian coolies were made to carry heavy loads from the plains since there were no roads. The “groaning coolies” were picked up from the villages and forced to carry heavy cargo, said the author.

In the 1830s, Emily Eden wrote in her diary Up the Country, “Every camel trunk takes eight coolies to carry and we had several hundred camel trunks.”

Ian Stephens wrote that the annual move to Shimla was romantic, but “rather horrifying”. Coolies pulled the rickshaws and the “terribly heavy loads” on their backs up the slopes.

Siddharth had read some of it before, but never felt a need for such detail. But Anjali had to for her research.

Appalling details of the sufferings of native workers engaged in the construction of road and rail links were recorded in some books.

“Why did it take us so many years

to get rid of the British?” Anjali asked artlessly. He smiled. She did not expect an answer, he knew.

He flipped through the entries. Impressive, Anjali had read through many of the numerous private diaries in the institute library.

Under the heading ‘History’, she had noted facts regarding the colonial era.

Shimla was transformed into a heritage town after the 1840s. Today, looking around the town was like flipping through a history book or exploring a museum stocked with archaeological treasures.

Some records said that Shimla was given to the maharaja of Patiala for the help he had offered the British in the war with Nepal. Which royal it was, the writer could not say. The maharaja had initially used the hills as a sanatorium.

One author mentioned in his book about an English officer who commanded the Ghurkha troops in those days as the first Briton to realise the potential of Shimla.

According to another story, two Scots, the Gerard brothers, who were hired to survey the Sutlej valley in the early eighties, promoted Shimla among the English. British officers soon began moving to the hills during the summers on a regular basis, slowly transforming the Shimla village into a popular hill station and convalescent depot.

Shimla was officially declared the summer capital of the British India in 1864. Native chiefs copied this practice. The Punjab government started using the town as its summer capital from 1871.

Anjali had copied an amusing document in her journal, word for word, an announcement about the summer movement to Shimla during the period. She had titled it ‘Floating Population’, under which she had written:

Source: Revised Heritage Report

“Should the Governor General and Commander-in-Chief come up next season, it will consist of British subjects, 200, and native 8,000. When the tributary chieftains and followers come in, it will be nearly 20,000. Again in winter, when but few remain, it will probably not exceed British subjects, 20, natives, 2,000.”

How did they manage to move up to these heights summer after summer? Shimla was initially only accessible from Kalka, forty three miles up the hills, by horse carts operated by the Mountain Car Company. The Kalka-Shimla railway line was commissioned much later, only in 1904.

Siddharth looked at Anjali with an approving smile. She had indeed taken her assignment seriously.

He was impressed that she had managed to make such detailed entries in her journal.

He looked out the window. The guesthouse was near the Ridge, and it gave a good view. The British Simla used to stretch along the Ridge between Jakhu and Prospect Hill; another century.

Many decades after the British had left for good, their descendants still visited Shimla in search of their roots. That was curious. Maybe he could develop the idea into a special story for his magazine.

“How about some mall walking?” she proposed the next morning.

Anjali looked fresh and eager to indulge in window shopping. Trinkets and books; he was familiar with her obsessions. What pleasure did she get in these mementos, as she called them?

“We call it comfort shopping. Indulgence is a real mood elevator,” she said. “It’s like pampering your ego, you see.”

“OK, OK, I see…,” he said, laughing, amused at her enthusiasm.

He looked up when Anjali clasped his arm as they climbed to the Lower Bazaar of the Mall Road. The drizzle made the climb tricky. The connecting road was covered with slush, slowing down their pace. They crossed the busy road, past the parked tourist buses. The tour conductors called out to vacationers the names of places of interest in Shimla and elsewhere in Himachal, such as Dharamshala and Manali.

Anjali walked along the stone-paved edge of the path. The narrow lane to the Tibetan Market ended in a steep climb. The Tibetan Market was one of her favourite shopping spots for trifles.

“Let’s enjoy the sun for a while,” she suggested with the excitement of a child when they reached the Ridge.

The Ridge, the heart of Shimla, was the hub of cultural activities and the venue for celebrations. He recalled how it had come alive during the Shimla Summer Festival a month ago.

The large open space ran alongside Mall Road, and stretched between Scandal Point on the west and Lakkar Bazaar crafts market on the east. The Telegraph Office was on the west end. The iconic grey stone building, the Town Hall, was the centrepiece of the Ridge. He had become thoroughly familiar with the area as a Shimla correspondent during his newspaper days, years ago. The place was close to his heart ever since school days, having captured most of his childhood memories here.

As they walked through the Upper Bazaar a little later, Anjali talked animatedly about her life at the institute, the discussions in the evenings with fellow researchers, and the books she had read between his visits. He heard most of what she said. The rest of the time, he saw only a flurry of emotions on her face, rising and passing like light and shadow across the hills on an overcast day.

Once a British-only street, six-kilometre long Mall Road was now a popular tourist attraction. Somewhere during the 1850s, civic buildings came up along the road, which remained an auto-free zone. The road kept the colonial past alive with its unique railings, street lights, staircases, wrought-iron benches and stone-paved roads. Many of the stately emblems were sadly missing from the majestic banisters.

One of the important British-era landmarks, the Gaiety Theatre, had recently been restored to its past glory.

Gaiety was part of the five-storey structure, the Town Hall, which used to be the tallest building in those days. The design won the Bijou Theatre Award from the Dramatic Society of London. It was the only theatre in Asia with an authentic Victorian hall and stage, with high-pointed arches, ribbed ceiling, and flying buttresses that showcased Gothic architecture.

The architectural spectacle, with flawless acoustics and unique features, was the hot spot of theatre lovers. It was frequented by patrons, professional artists, and amateurs.

The theatre hosted musical performances and original plays. Writers such as Rudyard Kipling had performed at the Gaiety. Kipling had played a character in A Scrap of Paper, Siddharth had read in a recently published book on Shimla.

The same book mentioned a funny incident that marked the first performance at the Gaiety, with a play entitled Time will Tell. One actor, who was playing a female character, refused to shave off his moustache, creating a scene. In another instance, a charity show had to be cancelled at the eleventh hour, as the lead actor was too drunk to perform. Surely, those were interesting days.

Anjali had listened wide-eyed when he told her about the slow transformation of the theatre during his previous visit.

A short distance away from the Ridge was the quiet Summer Hill, where Mahatma Gandhi had lived during his visits to Shimla.

On one corner of the Ridge was the library, a favourite spot of the locals. Edifices such as the Christ Church, the second-oldest church in north India, added romance to the space. The stained-glass windows of the church and its pointed arches were reminiscent of the British taste and the crowd that would have once frequented the place.

A few steps down the Ridge and a short distance away was the Ladies Park, also known as Rani Jhansi Park, open exclusively to women and children.

The modest restaurants tucked into the sides of the stairs leading to the Lower Mall from the Ridge served Himachali food. The mashed dal and the spicy kidney beans cooked with curd were Anjali’s favourites.

The Lower Mall was made up of tiny shops perched on either side of the narrow lane. It was a place where he would not normally loiter, but Anjali’s company made the congested place rather interesting.

Her presence did something pleasant to him. He felt younger and relaxed. The office, pressing engagements, and the overbearing presence of his wife; all faded. He was just him, the adventurous Siddharth that he used to be before marriage. Anjali had changed his attitude towards life. But strangely, she seemed to be unaware of her effect on him.

Mall Road was not crowd

ed. Anjali checked out the ethnic jewellery collection at the handicrafts shop.

The Upper Bazaar had changed over the years. It now had tourist dens, such as pizza joints, bookstores, and memento shops.

The Indian Coffee House was the favourite spot of journalists and office workers, mostly men. Siddharth wanted to avoid the coffeehouse. There was a strong chance that he could bump into some old acquaintance. It was a popular hangout for local men and visitors alike.

While climbing the stairs that led to the Upper Bazaar, Anjali stopped and held his forearm. “I’m tired,” she huffed out of exertion. They had been walking for the most of the afternoon. Siddharth, too, was feeling tired after climbing the numerous steps between the two bazaars.

“Siddh, haven’t you forgotten something?” asked Anjali as they walked towards the hotel.

He looked at her, making a futile attempt to guess.

“It’s my birthday. You couldn’t guess even after I gave you a hint. I thought your visit was a birthday surprise for me,” she complained, lips drawn side in a frown.

“Oh, no! It escaped my mind,” he regretted the slip. “I don’t remember birthdays or anniversaries. Chandni keeps a track. But she doesn’t complain like you.” He only meant to distract her. But it did not work that way.

“I’m not so perfect, Siddh. I am not as understanding or wonderful as your wife. I’m too ordinary. I feel sad, hurt, and angry when things don’t work my way,” she said, her voice choking.

Siddharth realised his mistake. He should not have mentioned his wife. Anjali was too sensitive. He felt stupid.

“Let’s go back and buy something for the birthday girl,” he tried to cheer her up.

It worked. She brightened up and led him to the Himachal Pradesh handicrafts shop.

“Show me earrings, the large ones the hill women wear,” she told the salesgirl at the jewellery section.

After searching the collection for a while, Anjali selected a large pair of metal earrings with intricate carvings. Siddharth found her interest in ethnic jewellery curious.

The Plunge

The Plunge